In

Foreign Affairs Magazine HomepageExploreMy AccountSign InSubscribeSign in

Can Vietnam Help America Counter China?

The Limits—and Hidden Strengths—of Washington’s New Partnership

By Derek Grossman

October 6, 2023

Sign in and save to read laterSend by emailShare on TwitterShare on FacebookShare on LinkedInGet a linkPage urlRequest Reprint Permissions

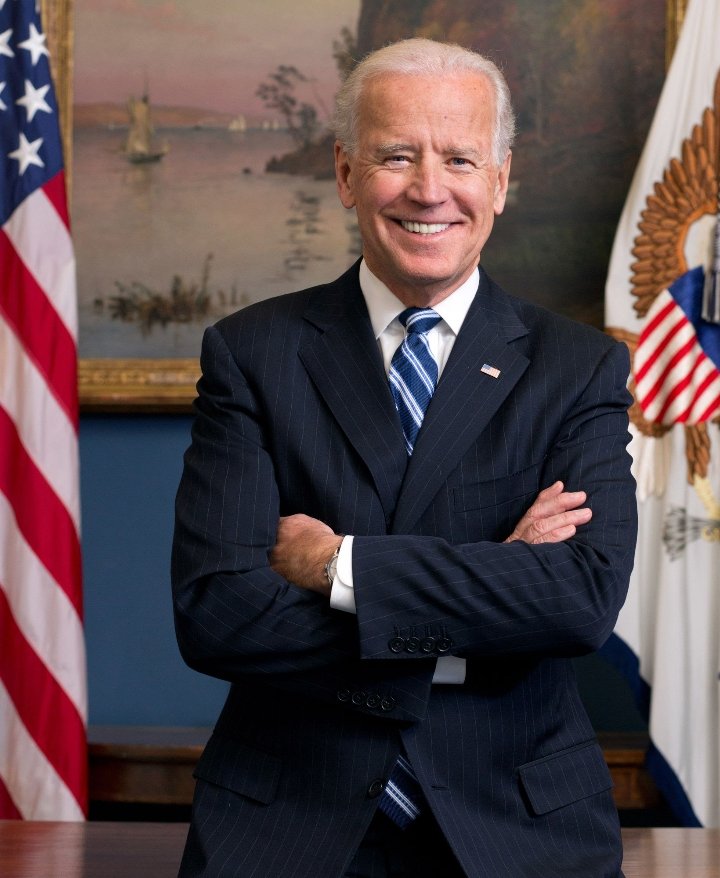

In the weeks since U.S. President Joe Biden traveled to Hanoi to announce a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with Vietnam, many commentators have described it as a historic turning point in U.S.-Vietnamese relations. The partnership is the highest kind that Vietnam recognizes with foreign powers, and it has come at a time when the Biden administration is particularly eager to draw Hanoi into its broader Indo-Pacific strategy to counter China. In this reading, by agreeing to elevate the partnership, the Vietnamese government appears to be aligning itself with, or at least tilting toward, U.S. priorities in the region.

The deal was certainly historic. After all, the United States and the communist government of Vietnam, former foes, did not normalize relations until 1995 and have approached each other warily for much of the time since. But their new partnership coincides with growing concerns in Hanoi about Beijing. In recent years, Vietnam has become apprehensive about growing Chinese assertiveness not only in the South China Sea, where it maintains overlapping sovereignty claims with China, but also along the Mekong River, where Chinese dams upstream have created serious food and resource insecurities downstream in Vietnam.

Still, the geopolitical consequences of the new U.S. partnership should not be overstated. For one thing, Hanoi has had close relations with Beijing dating back to the colonial period, when the Chinese Communist Party helped its Vietnamese counterpart oust the French occupiers. Later, China supported Vietnam’s fight against the Americans. To this day, and in spite of overwhelming anti-Chinese sentiment in the Vietnamese People’s Army and among the Vietnamese population—borne out of multiple Chinese invasions over the millennia—the ruling Vietnamese Communist Party continues to maintain friendly relations with Beijing. Indeed, since 2008, China has been a comprehensive strategic partner with Vietnam in its own right. Moreover, Vietnam’s long-standing approach of nonalignment has not changed, and the country will almost certainly maintain deep and expansive ties to China and other countries of concern to Washington, namely Russia.

As a result, it is crucial now for Washington to test the extent to which Vietnam is willing to contribute to the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy to counter China and determine the areas in which it can tangibly bolster Hanoi’s economic and military security against its far larger neighbor. As Hanoi’s balancing makes clear, there are some clear limits to the relationship, but there are also ways for the United States and Vietnam to expand their collaboration.

FOUR NOS AND A MAYBE

In the fading afterglow of Biden’s September visit to Vietnam, Washington is likely to soon discover the limits of the new partnership. Hanoi will be hesitant to go much further than it has already gone in joining with the United States in countering China. For Hanoi, the elevation of ties to “comprehensive strategic partnership” is more about signaling to China the strength of U.S.-Vietnamese relations than about creating an actual framework for enhanced security cooperation with Washington. Strategic partnership designations simply denote that Vietnam and the partner country share what Vietnamese policy analysts describe as “long-term mutual interests,” and do not necessarily involve the procurement of new military capabilities or additional forms of joint security cooperation. The largely symbolic nature of the designation holds true with all of Vietnam’s other comprehensive strategic partners, including China, India, Russia, and most recently, South Korea (which earned the status in December 2022).

Moreover, Vietnam’s decision to elevate its partnership with the United States must be viewed through the lens of its self-proclaimed “bamboo diplomacy.” Coined by Vietnam’s leader, General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, in 2016, bamboo diplomacy—a firmly rooted yet flexible and resilient approach to international politics—amounts to a hedging strategy that allows the country to navigate a polarized, great power–dominated world without compromising its sovereignty and independence. Since Russia invaded Ukraine, for example, Hanoi has used bamboo diplomacy to preserve relations with Moscow as well as with Kyiv and the West.

Thus, although Hanoi has opposed or abstained on votes criticizing Moscow at the United Nations, the Vietnamese envoy to the UN has also implicitly chastised Russia’s behavior by highlighting the “obsolete doctrines of power politics, the ambition of domination, and the imposition and the use of force in settling international disputes.” Vietnam has also pledged $500,000 of humanitarian assistance to the Ukrainians. And yet, according to a recent report in The New York Times, Vietnam may be negotiating a secret deal with Russia for additional military arms, possibly in contravention of Washington’s Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act. The bottom line is that Vietnam’s foreign policy certainly can and does play both sides of international issues to secure its interests.